LOCAL PRODUCTION

Northeast Ohio & the Great Flood of 1913

Residents view three houses destroyed by the flooded Cuyahoga River on Lods Street in Akron in 1913. Photo courtesy of the Summit County Historical Society.

PBS Western Reserve (WNEO 45.1 / WEAO 49.1):

Friday, Nov. 7, at 9 PM

Saturday, Nov. 8, at 2 AM

Thursday, Nov. 13, at 8 PM

Friday, Nov. 14, at 1 AM and 5 PM

Sunday, Nov. 23, at 1 PM

Fusion (WNEO 45.2 / WEAO 49.2):

Saturday, Nov. 8, at 2 PM

Monday, Nov. 17, at 10 PM

Saturday, Nov. 22, at noon

The weather in Northeast Ohio on Easter Sunday in 1913 was supposed to be “generally fair” and cool. The Akron Beacon Journal counseled readers that they could “bring forth your Easter finery.” But, as folks left church that Easter morning, a steady, chilly rain started, ruining bonnets, dresses and suits. The rain did not stop.

Over a four-day period, up to a foot of rain fell across Ohio — what came to be known as “the great Ohio flood.” The storm remains the worst weather disaster in the history of the state.

Estimates of the number of people killed in the flood vary from around 350 to more than 500, but many historians today believe those numbers are too low. The U. S. Geological Survey put the damage in Ohio at $143 million, about $4.5 billion in today’s money.

“Just about every city and town in Ohio suffered damages during the storm,” said NORTHEAST OHIO & THE GREAT FLOOD OF 1913 producer Fred Endres. “We focus on Akron and Kent in the documentary, and they tend to be fairly representative of what happened in other Northeast Ohio areas.”

The program includes dozens of photographs of the flood and flood damage in Akron, Kent and other nearby towns. Endres said he was amazed at the number and quality of images available through such organizations as the Akron-Summit County Public Library, Kent State University, the University of Akron, the Summit County Historical Society, and the Barberton Public Library.

“Those images really show the extent of the devastation and human suffering in Northeast Ohio and throughout the state,” said Endres, thanking local librarians and archivists. “They are unsung heroes.”

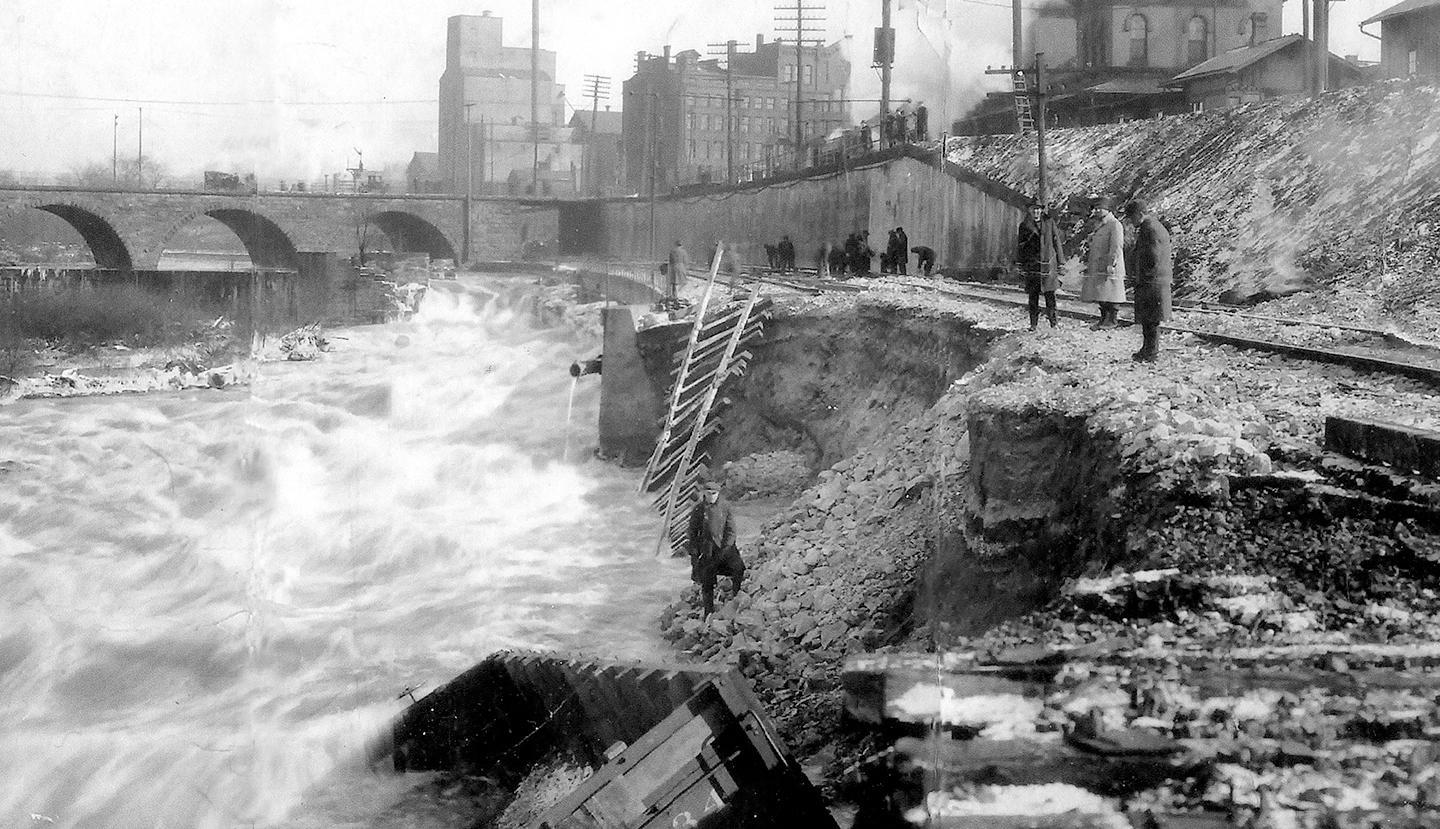

The raging Cuyahoga River in Kent, Ohio destroyed the Pennsylvania & Ohio Canal lock and the adjacent B&O railroad tracks in March 1913. Photo courtesy of the Kent Historical Society.

Q&A with Independent Producer Fred Endres

Fred Endres is an independent producer and longtime collaborator of PBS Western Reserve who focuses on local history in his documentaries such as SÉANCES & SLOT MACHINES: THE STORY OF BRADY LAKE PARK; UNDER FIRE, UNDER SIEGE: STRIKEBREAKERS IN KENT, OHIO; and AKRON, RINGLING & THE ‘BLUE HEAVEN’ CIRUIT. Endres is also a professor emeritus of the School of Media and Journalism at Kent State University, where he retired in 2014 after teaching for 40 years.

His latest project tackles the worst weather disaster in Ohio history. NORTHEAST OHIO & THE GREAT FLOOD OF 1913 premieres on PBS Western Reserve on Friday, Nov. 7, at 9 PM.

Q: You've distributed several documentaries through PBS Western Reserve over the years, primarily about local history. Do you consider yourself a historian?

A: I am a historian by inclination, interest and training. From my early work as a newspaper reporter through my current work as a documentary maker, I have been interested in history and have written about history. I studied historiography in my master’s and doctoral work. Local history has always been my focus. It is much more personal, to me, when I am telling the stories of people who lived and worked in my community.

Why is local history important to cover?

It’s important that folks have a sense of their community and their place in it. To understand and appreciate where you are today, you need a sense of where your community and the people in it have been in the past, what they experienced and believed.

It’s also important to me to tell the stories of people in the past. Each story becomes very personal to me. I feel I know my subjects. A number of years ago, when I was making a documentary on seven local soldiers during the Civil War, I got to know them very well as I read their letters and diaries and learned about their families and comrades. I knew them as young men and women under severe stress. It was very hard for me when, at the end of my research and writing, I visited their graves and realized that they had been dead for a hundred years. I felt like I had lost close friends.

What drew you specifically to the subject of the Great Flood, and why is now the right time to tell this story?

This was a mammoth disaster, across fifteen states. Ohio was one of the hardest states hit. I was struck by the enormity of the storm and the flooding and by the immediacy of the devastation. But, I also was struck by the resiliency of people across the state. They picked up the pieces and went on with their lives. That’s a remarkable human characteristic that repeats itself throughout history. The story of this flood becomes more important in the context of the horrible Texas flood and others in the past year or so.

What is your process like as an independent producer? Does it start with an idea, then the research comes after? Or does it start with research, and the idea follows?

The ideas are first. Then the research. And more research, and more research. Then the writing. Then the producing, finding visuals and music and commentators. Then the script editing; then the video production and editing. It is a long, enormous and isolated process. It is also the most fun I’ve ever had in my career as a journalist, teacher, multimedia producer and documentarian.

You’ve spoken about collaboration with local museums and libraries, calling them "unsung heroes." Are there any other collaborators that help to fuel your work?

Documentary producers could not do their work without the efforts of archivists and researchers in libraries, archives and special collections. I have worked with these folks across the country. They are experts in their fields, and they are tireless in their efforts to help. They come up with some amazing materials. Some of the most helpful in this project were from the Akron-Summit County Public Library, Kent State University, the University of Akron, the Summit County Historical Society, Barberton Public Library, and the Kent Historical Society.

Other folks who have been invaluable in their assistance and collaboration over the years were my colleagues at Kent State and the University of Akron, as well as dozens of undergraduate and graduate students from the Journalism and History departments.

Discover the story of the worst weather disaster in Ohio’s history, the Great Flood of 1913.